The Icelandic Sheepdog

The history of the Icelandic Sheepdog is interwoven with the history of the nation. Ever since the Age of Settlement, this one true Icelandic dog breed has stood watch alongside the people, having been brought to the country by Norse settlers in the 9th century.

The Icelandic sheepdog was not only an indispensable working animal for herding and farming but also a loyal companion who helped people survive in a harsh land. It is because of this deep-rooted connection that the dog rightfully holds the title of Iceland's National Dog - a living cultural heritage that reminds us of our origins and perseverance.

This website is dedicated to that heritage; here, we share information about the breed's history and unique characteristics, and we collect treasured stories about our national dog.

The Icelandic sheepdog was not only an indispensable working animal for herding and farming but also a loyal companion who helped people survive in a harsh land. It is because of this deep-rooted connection that the dog rightfully holds the title of Iceland's National Dog - a living cultural heritage that reminds us of our origins and perseverance.

This website is dedicated to that heritage; here, we share information about the breed's history and unique characteristics, and we collect treasured stories about our national dog.

Blog

Lecture for ISIC – February 8

On February 8, I will give a lecture on Zoom about the history of the Icelandic Sheepdog through the ages. The lecture is organized by ISIC and will be held in English with the title "From Settlement to Survival: A Thousand Years of Iceland's National Dog". [Link to the lecture on February 8, 2026, at 7 PM.](https://zoom.us/j/99607892757?pwd=Y4zOwmVewna0R1qBaAu2a4fq3UNuSd.1#success) Since I have not previously mentioned ISIC, now might be the right time to explain what ISIC is. ISIC stands for Icelandic Sheepdog International Cooperation. Member nations are Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, the Netherlands, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Sweden, Germany, and the USA. _ISIC's main purpose is to support and encourage international cooperation in all matters that benefit, preserve, and protect the Icelandic Sheepdog._ Brief History In 1994, after many years of work, the Icelandic Kennel Club (HRFÍ) and the Icelandic Breed Club (DÍF) succeeded in convincing the Icelandic Parliament, Alþingi, that it was a national duty to preserve the Icelandic Sheepdog as an inseparable part of Icelandic culture. Alþingi tasked the Minister of Agriculture with appointing a committee to oversee the future and preservation of the Icelandic Sheepdog as Iceland's national dog. Guðrún R. Guðjohnsen, who was chairman of HRFÍ at the time, sat on the committee appointed by the Minister of Agriculture to oversee the Icelandic Sheepdog. When the majority of committee members felt they were ready to submit a final proposal, the HRFÍ board disagreed. They felt the proposal lacked essential basic information. Because of this, HRFÍ and DÍF decided to seek support abroad, especially from Sweden. With the help of the Swedish breed club, Islandhunden Sverige, the first international breed club support was obtained. In January 1996, a joint document was sent to the Nordic Kennel Union. This document was signed by breed clubs and representatives from six countries: Iceland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Finland. This marked the formal beginning of international cooperation on the Icelandic Sheepdog. I encourage everyone interested to explore [ISIC's website](https://icelanddog.org/), where there is much of interest to be found, including interesting lectures and presentations held over the years, important articles as well as annual reports from participating countries that provide excellent insight into the work of breed clubs and cooperation through ISIC. ISIC also maintains the database where all registered Icelandic Sheepdogs can be found. [See here.](https://www.islenskurhundur.com/Home) I look forward to talking about the history of our national dog and hope that many will find time to listen.

Colors of the Icelandic Sheepdog – registration is now open!

One of the projects we received funding for in 2026 is to create a photo database of color variations of the Icelandic Sheepdog. For this purpose, we have hired a photographer who specializes in dog photography to obtain high-quality images under consistent conditions. We will likely offer 4 photo sessions over the coming months, two in North Iceland and two in South Iceland. We want to capture images of all color variations of the Icelandic Sheepdog, which is why registration for the photo sessions is necessary. We will then select from the registered dogs to cover as many colors as possible and invite them to photo sessions on specific dates in both North Iceland and South Iceland. At the end of the project, we will set up a color database here on this website that will be useful for anyone interested in viewing the breed's colors, and a screen will also be installed at the Heritage Center to browse through the database. The project is funded by the Development Fund of Northwest Iceland. The photographer is Carolin Giese from [LinaImages](https://linaimages.com/gallery/dogs/). Would you like the opportunity to participate in a photo session with your dog and receive two high-quality digital photos for personal use? To participate, the dog must: be a purebred Icelandic Sheepdog with pedigree from HRFÍ have reached 12 months of age be "in coat" during the photo session and in good physical condition (not too thin nor too fat) have erect ears and a beautiful curled tail may be long-haired or short-haired be able to pose either naturally in free stance or with a show lead (the show lead will be removed from the photo during post-processing) Registration: Please [fill out the form here](https://form.jotform.com/260242659643359) if you are interested in participating.

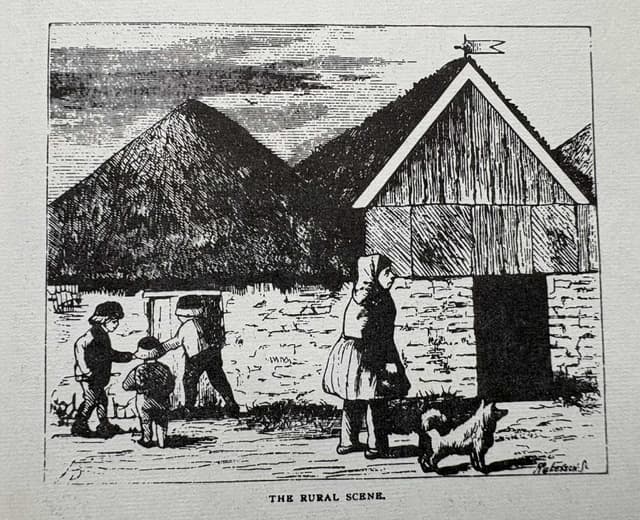

Where is this?

I'm always looking for old photos that show dogs. A while ago, I came across this beautiful photo that I'd like to share here. Every week, an old photograph is published on [Akureyri.net](https://www.akureyri.net/is/gamla-myndin) in collaboration with the Akureyri Museum to gather information about where and when the photo was taken, and who the photographer was. This photo shows an old turf building, or more accurately, a rather dilapidated outbuilding. Three boys (or two boys and a man?), one of them on a horse, and a dog are standing outside. The photo was published in August 2025 and no information has been received. If anyone recognizes this photo or location, please contact [Akureyri.net](https://www.akureyri.net/is/gamla-myndin/250-228-2025-veistu-hvar-thetta-er). If anyone reading this has old photos in family albums or on walls showing dogs in Iceland from the old days and is willing to let me have a (digital) copy of them - please contact me. There are so few photos available, and I'd like to make more pictures of dogs visible and preserve them.

Contact

Lýtingsstaðir, 561 Varmahlíð.

+354 893 3817

[email protected]